5 Things You Need to Know About Solidarity in Reconciliation: Calling in White Settler Canadians

written by Rebecca Tan

written by Rebecca Tan

You’re a non-Indigenous young person interested in reconciliation: changing the present-day and future relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. You genuinely care about engaging in cross-cultural dialogue about reconciliation respectfully and responsibly, and believe that you are truly well intentioned…so, what should you know?

You’re a non-Indigenous young person interested in reconciliation: changing the present-day and future relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. You genuinely care about engaging in cross-cultural dialogue about reconciliation respectfully and responsibly, and believe that you are truly well intentioned…so, what should you know?

1. If you’re driven by guilt, you’re not ready

You should be well aware that as a country, Canada was established through a process called colonialism*. Colonialism has built institutions and structures, systems, that continue to shape and govern present-day society and subsequently continue to harm, ignore, or disadvantage Indigenous people to the benefit of non-Indigenous groups (that’s privilege).

Maybe you’re feeling overwhelmed by the complexity of these issues, and feeling kind of guilty. After all, you’ve never really had to worry about the actual impacts of these issues in your daily life (and this is not coincidental, since the systems were built that way).

If you’re motivated by guilt, you’re not ready to live in solidarity with Indigenous people and communities. You’re consciously unpacking what it means to be privileged, which is an excellent start. But in order to contribute to changing these systems, you need to be able to think at a systems (macro) level, which means being able to reflect critically on your positionality without fixating on it (which in itself, is privilege). Guilt is an individualistic and internalized experience that centers you — rather than those whose lives are directly and violently impacted by oppressive systems. Your guilt might demonstrate an astute level of mindfulness; but absolving it can’t be your only interest in solidarity work. For more, refer to this excellent piece by Harsha Walia.

2. Indigenous voices,experiences, and needs should be at the centre of conversations around reconciliation

Be aware of your privilege; you’re not the centre of attention here.

For too long, the voices, experiences, and needs of Indigenous youth and communities have been silenced or ignored. Non-Indigenous and settler Canadians have not been listening, have spoken for communities they do not belong to, or have not been invited to speak altogether. This is a demonstration, once more, of privilege: a sense of entitlement to do the speaking, based on the assumption that you will be heard and believed. In the process of reconciliation, be aware that any time you as a white settler Canadian decide to say something, you hold and take up space. That is to say: every moment you are speaking is a moment that someone else, an Indigenous youth, could be talking instead.

You’ve heard of the saying, “nothing for us without us”? In any cross-cultural conversation about reconciliation, Indigenous voices should be prioritized, and any knowledge shared by Indigenous communities should be valued and respected. This does not mean if you hear something that it then belongs to you, or that you have permission to share it. Ensuring that Indigenous truths are meaningfully heard, and acted on in partnership with Indigenous communities, is essential towards changing Indigenous and non-Indigenous relationships. Active listening is an important skill to have and it is a conscious choice to practice.

3. You’re uncomfortable, not unsafe

You’re in a conversation, attempting to practice active listening and something comes up that makes you feel uncomfortable. You’ve heard about safer spaces, and are now wondering: has my safe space been compromised?

In short, no.

Safety in a space that is intended for cross-cultural dialogue does not mean comfort for the privileged. It’s meant to establish the parameters to make it possible for Indigenous and other marginalized youth to engage in courageous conversation about their experiences, share their stories and speak to their needs–not yours.

What you are experiencing is discomfort; you are not in a space that is unsafe. You are simply in a space that does not place you at the centre and cater to your needs, which may be new for you if you’re used to that privilege. As you’re coming to terms with your privilege, unlearning, and figuring out your role in reconciliation, you’re going to inevitability find yourself in uncomfortable situations. While these are opportunities for personal growth, it’s important to understand your boundaries and seek out ways to process your learning if need be. But do not expect Indigenous and racialized youth to do that work for you. Do not expect them to support you through your discomfort.

4. You’re taking up space, even if you’re “just listening

Indigenous people are not obligated to share their knowledge, feelings, or experiences with you or other non-Indigenous people. If they do, listen and learn with respect, not a sense of entitlement.

There is a real need for spaces to discuss challenging and complex topics, to talk about trauma and resistance. These spaces need to be rooted in trust and safety within communities. Sometimes, this means that communities will not want you to be part of the conversation. There are conversations Indigenous youth may want and need to have before entering “cross-cultural dialogue.”

In these instances, as a white settler Canadian, you will need to practice great care to ensure that you respect the boundaries that communities may set for themselves. You do not have to be a part of every conversation.

In solidarity work rooted in resistance to oppressive systems and institutional racism, some communities may better understand and have a significantly more pressing need to have conversations around shared experiences because of their intersecting lived realities. It’s important that Black, Indigenous and People of Colour (BIPOC) build community with one another and that their space to discuss solidarity is respected. There is great diversity in communities constituting the “non-Indigenous” side of the Indigenous/non-Indigenous relationship in Canada. Spaces need to be held for Black and People of Colour (POC), prior to larger cross-cultural conversations.

If you are not invited to these conversations, you may feel uncomfortable. You will need to learn to respect the needs of communities. Sometimes solidarity means not being part of the conversation.

5. Live solidarity, instead of self-imposing labels

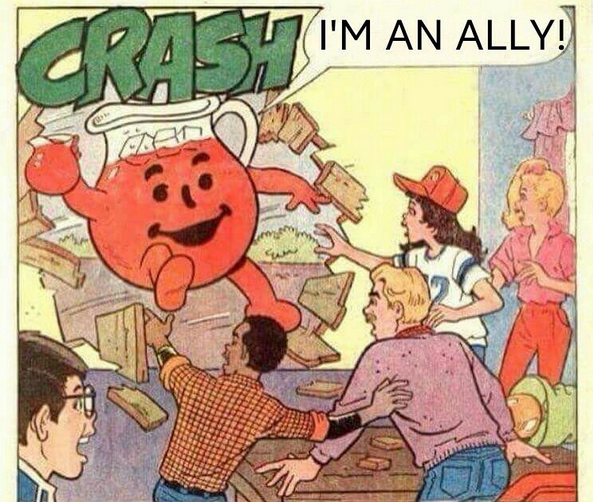

Finally, let’s talk about being an “ally”. You’ve noticed that I’ve gone through most of this post without mentioning this word once. And that’s because this piece is about solidarity.

The “ally” identity is a chosen and often self-appointed. And because it is a privilege to be able to decide for yourself if you want to be involved in solidarity work, be careful about labelling yourself an ally. As Jay Dodd writes, being an ally means refusing “to take praise for defending people, stories and experiences that should not have to be defended.” As he also notes, the moment that you do, your privilege is re-enforced and a decentering of Indigenous voices in the conversation has occurred. For more, read his article on the Myth of Allyship.

Ultimately, what you should know about living in solidarity with Indigenous peoples (towards reconciliation) is that there is a need to decenter your desire for comfort and control, understanding that solidarity work is not about or for you. You will make mistakes. Be willing to apologize, learn, and be informed in the choices you make. This will require a lot of work before you even approach cross-cultural dialogue at all. Be willing to do your homework. Don’t ask Indigenous people to do it for you. Approach and enter spaces with care, listen carefully and back your good intentions with your actions.

* Many Canadians are not aware of this, as Ryan McMahon recently pointed out in his blog post Dear Canada: You Need a Statement of Facts if You’re Going to Address Indigenous Issues.

Rebecca Tan was a volunteer member of the Resource Development Committee that worked on the 4Rs Framework for Cross Cultural Dialogue. She is passionate about communicating narratives of place through the inclusive design of public spaces and built form.

Wiidookaagewag Bimaadzijig: Building an Indigenous Accompliceship

Wiidookaagewag Bimaadzijig: Building an Indigenous Accompliceship